Repair of Primary Retinal Detachment: Review of Techniques for Repair Developed in the Past 85 Years

- Автор: Super User

- Категорія: №1 (08) 2018

- Опубліковано: 31 серпня 2018

- Перегляди: 5493

https://doi.org/10.30702/Ophthalmology.2018/08.06

Prof. Ingrid Kreissig, MD, Prof. h. c.

Department of Ophthalmology, Medical Faculty Mannheim of University of Heidelberg, Germany

The Keynote Lecture – dedicated to Prof. Harvey Lincoff, MD who had passed away November 25, 2017 –, was delivered during the International Conference “Vascular and Endocrine Eye Pathology”, at Kiev, Ukraine, March 1, 2018.

In the subsequent review I will present the various techniques for repair of a primary retinal detachment, which developed over the past 85 years in reattaching the retina.

The 1st conceptual progress in the treatment of a retinal detachment was made by Gonin in 1930 [1]. He postulated that a break is the cause of a retinal detachment. He applied Ignipuncture around the break. The reattachment rate increased from practically 0 % to 57 %.

However, this precise localization of the break was very difficult and therefore, already in 1931, Guist and Lindner [2, 3] circumvented this precise localization of the break by placing many diathermy coagulations – and this as a kind of barricade – posterior to the break to prevent a redetachment. In 1932 Safar [4] placed short perforating pins in a bar or single in a semicircle posterior to the break and touched them with a diathermy electrode to create a barrier or a so-called barricade of coagulations. Drainage occurred when the pins were removed. With this barrier operation retinal reattachment increased to 70 %, but redetachment occurred again. Why? Because the retinal break was not sealed off sufficiently.

The 2nd conceptional progress in the treatment of a retinal detachment evolved with Rosengren in 1938 [5]. He limited again the coagulations to the area of the break, but in addition after drainage of the subretinal fluid, he added an intraocular air bubble to tamponade the break abinterno. Thus, retinal reattachment increased to 77 %, and this was already the case in 1938!

But redetachments occurred again. – Why? – Because the air had left the eye too early, that means, before a sufficiently strong retinal adhesion around the break had developed and therefore, the break started to leak again. Another problem was also – as already experienced earlier – the precise localization of the break, which implied:

– limiting the coagulations exactly to the area around the break,

– but this was difficult, – somehow too difficult.

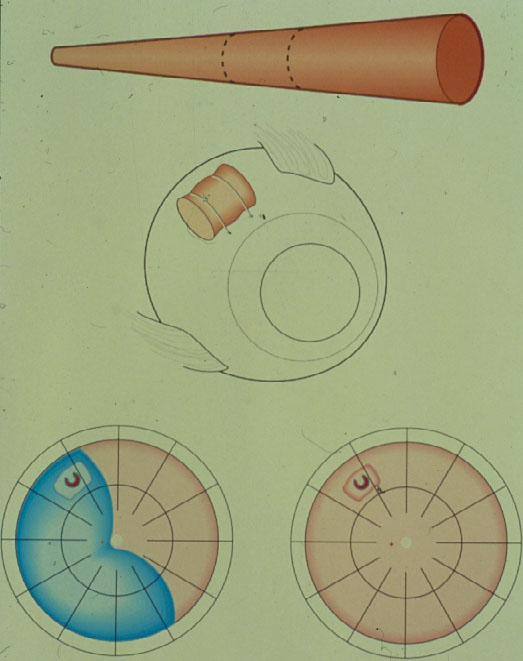

Therefore, again a surgery with more extensive coagulations was applied – Why? – To provide a barricade posterior to the break. But this time a scleral resection was added in the area of the coagulations and subsequently a plombe was embedded into the resection with the aim to create a high wall. To prevent future leakage of the break, in addition several lines of coagulations were added from the buckle towards the ora serrata (Figure 1).

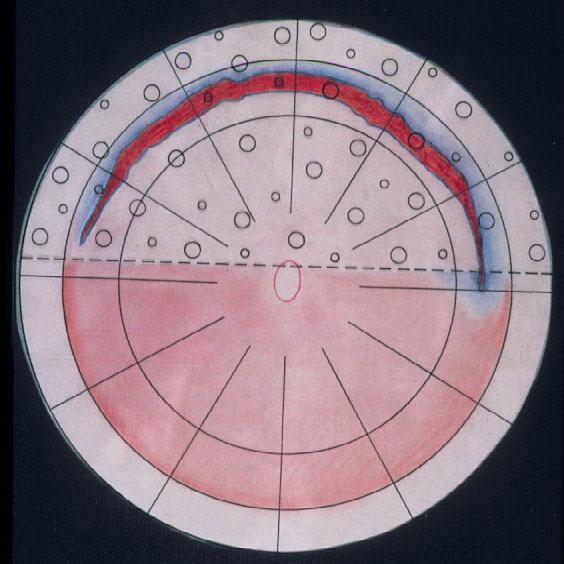

Figure 1. Segmental plombe from 12 to 5 o’clock with the retinal break positioned on the anterior edge of the buckle, surrounded with diathermy coagulations; against subsequent leakage of the break additional coagulations on the entire buckle and several so-called coagulation barriers towards the ora serrata. (From Primary Retinal Detachment: Options for Repair by Ingrid Kreissig (ed): Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005, 9:179, Figure 9.2a)

But, since the break was not tamponaded anteriorly, – what was to be expected? – the break started to leak again, the detachment crossed the barricades of coagulations, descended behind the buckle inferiorly, crossed it finally, and redetached the posterior retina (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Retinal break starts to leak anteriorly, resulting in a redetachment anterior to the buckle which subsequently crosses the various barriers of coagulations and finally progresses towards the posterior retina, resulting in redetachment. (From Primary Retinal Detachment: Options for Repair by Ingrid Kreissig (ed): Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005, 9:179, Figure 9.2b)

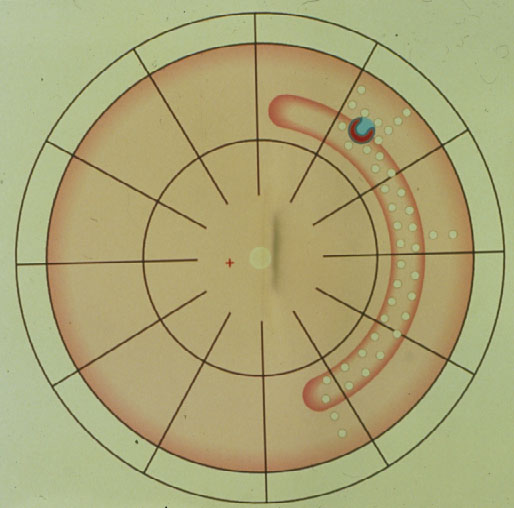

Thus, in 1953 Schepens [6] introduced the circular buckle, the so-called cerclage.

This operation is done with drainage of subretinal fluid.

The Cerclage is the 1st procedure still in use today for repair of a retinal detachment (Figure 3). It represents a maximum of barricade for the leaking break towards posteriorly. With the cerclage operation > 80 % of retinas were reattached, but recall, the retina is reacting logically to a still leaking break not being completely tamponaded, and this remained the main cause of redetachments. Subsequently in 1977 Pruett [7] added a wedge-buckle to the cerclage for a sufficient tamponade of the break.

Figure 3. Circular buckle (so-called cerclage) with coagulations spread over the entire buckle and anterior to it with a starting redetachment descending anteriorly of the buckle, crossing the barriers of coagulations, but due to the more posteriorly located cerclage, the larger amount of subretinal fluid having a greater momentum of progressing, subsequently is crossing the cerclage inferiorly and moving towards the posterior retina. (From Primary Retinal Detachment: Options for Repair by Ingrid Kreissig (ed): Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005, 9:180, Figure 9.3c)

But at this point some of you might ask: When there is just needed a sufficient tamponade of the break, provided by the wedge, why there is still added a circular buckle?

The 3rd conceptional progress in the treatment of a retinal detachment was made by Ernst Custodis in 1953 [8] (Figure 4). He limited again the surgery to the area of the break. His procedure consisted of: Full-thickness diathermy and an elastic polyviol plombe fixated on the sclera in the area of the break, but – for the 1st time – the detachment operation was done without drainage of subretinal fluid. How was this possible?

|

|

Figure 4. Ernst Custodis introduced 1953 the treatment of retinal detachment with an elastic polyviol plombe, diathermy around the break and without drainage of subretinal fluid. There occurred serious postoperative complications

This was made feasible by using an elastic plombe. However, unexpected serious postoperative complications had developed, which were caused by the toxic polyviol plombe in combination with full-thickness diathermy of the sclera. There were suddenly reports about: A postoperative scleral abscess, an endophthalmitis and even an enucleation, and this – so regrettable – was the end of the Custodis procedure in Europe and as well in America.

However, this was not the case for everybody in America, at least not for Harvey Lincoff in 1965 (Figure 5) [9, 10]. He, with his open mind for new developments was convinced of the rational approach of this new Custodis technique and therefore, he searched for means to avoid the reported postoperative disastrous complications of this new procedure.

Figure 5. Harvey Lincoff introduced 1965 the modified Custodis procedure by replacing the diathermy with cryosurgery, the polyviol plombe with the elastic tissue-inert sponge and could sustain by this the great advantage of nondrainage

In 1965 [9] he replaced the elastic polyviol plombe by the tissue-inert elastic sponge and in addition the necrotizing diathermy by cryosurgery [10].

However, cryopexy was not at all accepted. Why? Because there were great doubts about its adhesive strength. Therefore, from 1969 to 1972 when Ingrid Kreissig was working with Harvey Lincoff in New York, the open question about the adhesive strength of the cryosurgical adhesion was addressed by extensive animal experiments over 3 years consisting of 336 rabbit eyes in comparison to diathermy [11, 12]. It could be confirmed that:

– the cryosurgical adhesion is sufficiently strong after 7 days;

– and that it reaches its maximum of strength at 12 days. In addition it was found that

– it is possible to produce with cryosurgery – when the lesion is applied under ophthalmoscopical control:

A light lesion with a resulting light adhesion, a medium lesion with a medium adhesion and a heavy lesion with a strong adhesion, that means: There can be produced cryosurgical adhesions of different strengths.

Now back to the buckling surgery, being limited to the area of the break and without drainage of subretinal fluid. But soon it was realized that:

– the spontaneous retinal reattachment only occurred postoperatively, if all of the breaks were found and buckled sufficiently. Therefore,

– detecting all of the breaks had become the main goal of diagnostics, because this was the premise for success without drainage of subretinal fluid.

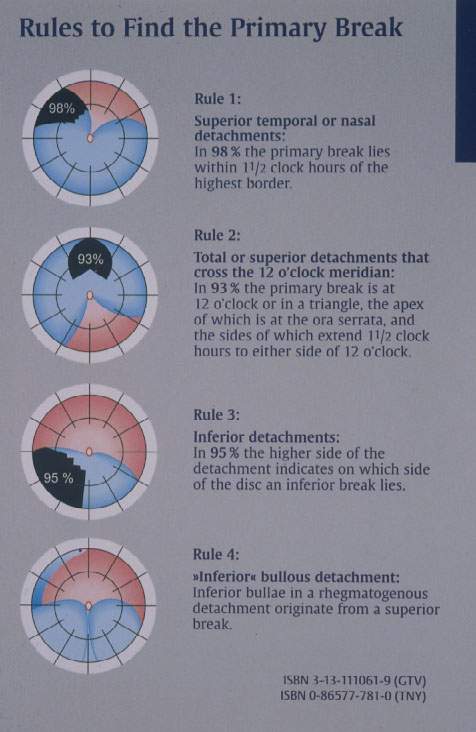

Therefore, after analysing the drawings of 1.000 retinal detachments, in 1971 Lincoff and Gieser [13] defined the Rules where to find the hole in a primary retinal detachment. These Lincoff Rules are still today essential for every retinal and vitreous surgeon (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The 4 Rules to find the primary break in a retinal detachment (From A Practical Guide to Minimal Surgery for Retinal Detachment: Diagnostics, Segmental Buckling without Drainage, Case Presentations by Ingrid Kreissig. Thieme Stuttgart, New York, 2000; back cover)

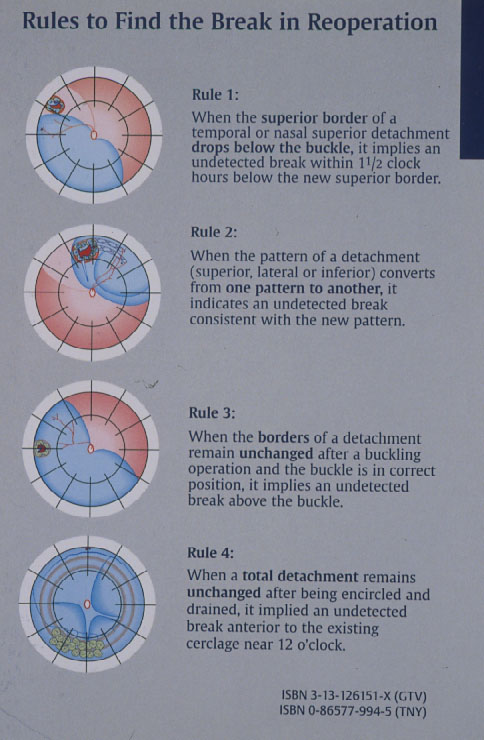

Subsequently in 1996 Lincoff and Kreissig [14] defined additional 4 Rules: How to find the missed break in an eye up for Reoperation (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The 4 Rules to find the missed break in a retinal detachment up for reoperation. (From A Practical Guide to Minimal Surgery for Retinal Detachment: Temporary Tamponades with Balloon and Gases without Drainage, Buckling versus Gases versus Vitrectomy, Reoperation, Case Presentations by Ingrid Kreissig. Thieme Stuttgart, New York, 2000, back cover)

The 4th conceptional progress for repair of a retinal detachment was made by defining these 8 Rules how to find the retinal break in a primary detachment and in an eye up for reoperation.

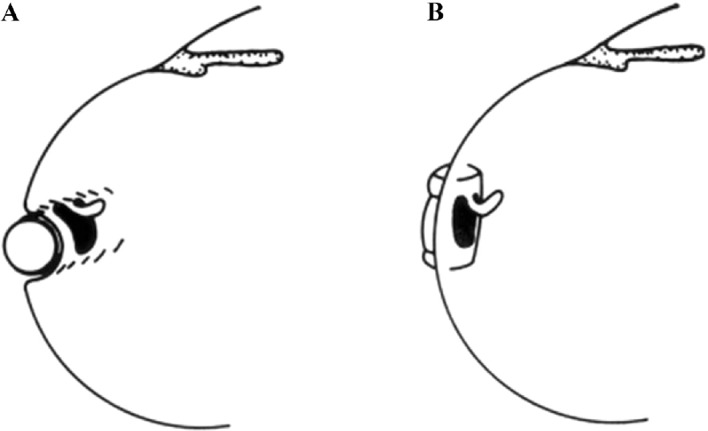

In addition in 1975 Lincoff and Kreissig found, that a break is better tamponaded by a radial buckle than a circumferential buckle, because posterior fishmouthing and anterior leakage of the break can be circumvented by this (Figure 8) [15].

Figure 8. Optimal orientation of a segmental buckle for tamponading a horseshoe tear: Using a circumferential buckle (A), the horseshoe tear is not tamponaded adequately. The operculum, an area of future traction, is not on the ridge of the buckle, but on the descending slope. In addition, there is a risk of a posterior radial fold, so-called fishmouthing, with subsequent leakage of the tear. Using a short radial buckle (B) provides an optimal tamponade for the horseshoe tear. The entire tear is positioned on the ridge of the buckle, i.e., this counteracts posterior “fishmouthing” of the tear and provides an optimal support for the operculum, counteracting at the same time future anterior vitreous traction. (From A Practical Guide to Minimal Surgery for Retinal detachment: Diagnostics, Segmental Buckling without Drainage, Case Presentations by Ingrid Kreissig. Thieme Stuttgart, New York, 2000; 8:141, Figure 8.6)

All of this resulted in a further refinement of the cryosurgical detachment operation without drainage.

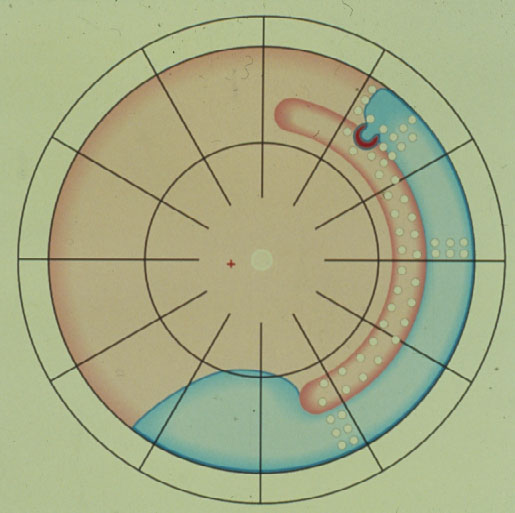

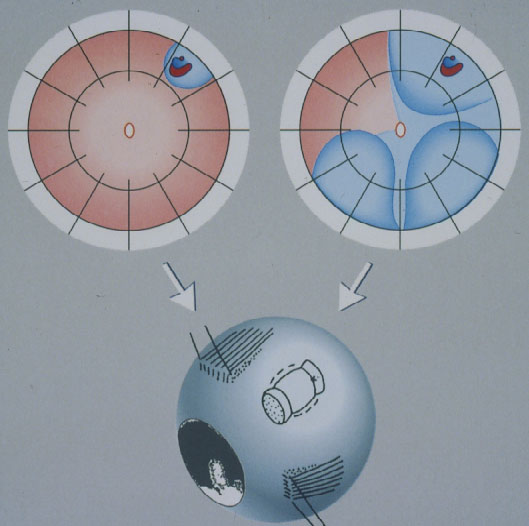

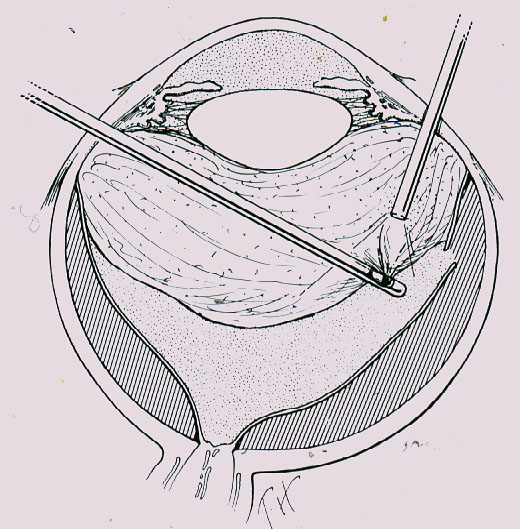

Minimal Segmental Buckling without Drainage or Minimal Extraocular Surgery is the 2nd procedure still in use today for repair of a primary retinal detachment (Figure 9). It consists of cryopexy and a sponge, limited to the area of the break, without drainage of subretinal fluid [16, 17]. Retinal reattachment increased after 1 operation to 93 % and after 1 reoperation to 97 %. After this localized procedure without drainage, PVR as cause of final failure was reduced to 1.9 %.

Figure 9. Minimal segmental buckling without drainage, so-called extraocular minimal surgery: The treatment is limited to the area of the break and not determined by the extent of the detachment. The small (top left) and the more extensive detachment (top right) are caused by the same horseshoe tear at 1:00. The treatment of both detachments is the same, consisting of buckling the tear either by a segmental sponge (as depicted) or a temporary balloon without drainage of subretinal fluid. (From A Practical Guide to Minimal Surgery for Retinal Detachment: Diagnostics, Segmental Buckling without Drainage, Case Presentations by Ingrid Kreissig. Thieme Stuttgart, New York, 2000, part of front cover)

Yet to reduce the surgical trauma even further, in 1979 the elastic sponge buckle was replaced by a temporary elastic balloon plombe with no intrascleral sutures for fixation and as well without drainage of subretinal fluid. This balloon operation is the most atraumatic procedure.

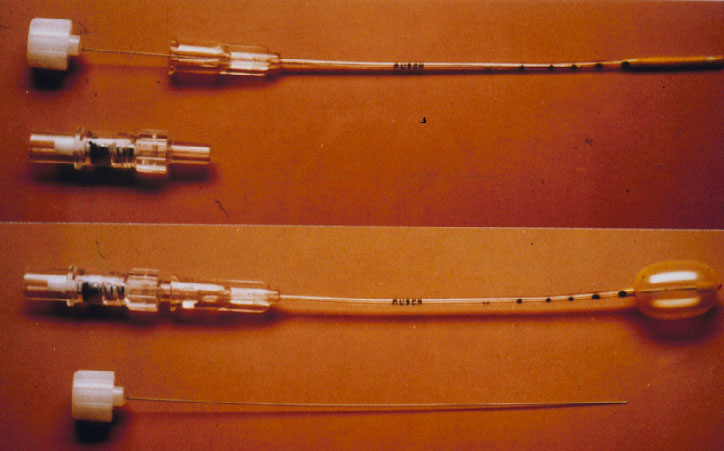

The 5th conceptional progress in the repair of a retinal detachment was made by the Lincoff – Kreissig Balloon Operation (Figure 10) [18].

Figure 10. Lincoff – Kreissig Balloon. The presented balloon has (1) a metal stylette to facilitate insertion into the parabulbar space and (2) calibrations (black marks) on the tube to enable a more precise determination of the balloon’s position in the parabulbar space. Deflated balloon catheter with stylette in place; beneath it the adapter (top). Inflated balloon (0.75 ml of sterile water) with self-sealing valve in place; beneath it the withdrawn stylette (bottom). (From A Practical Guide to Minimal Surgery for Retinal Detachment: Temporary Tamponades with Balloon and Gases without Drainage, Buckling versus Gases versus Vitrectomy, Reoperation, Case Presentations by Ingrid Kreissig. Thieme Stuttgart, New York, 2000, 9: 5, Figure 9.1)

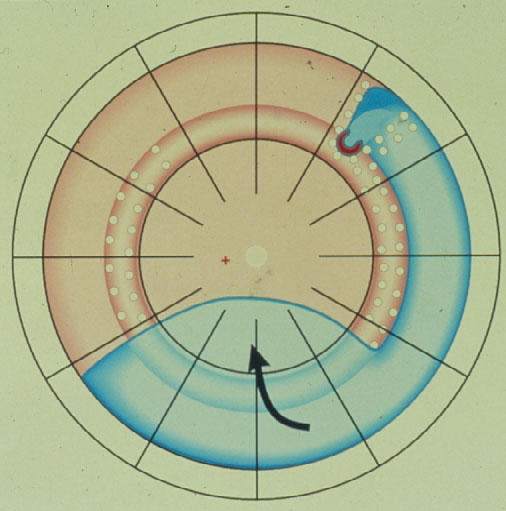

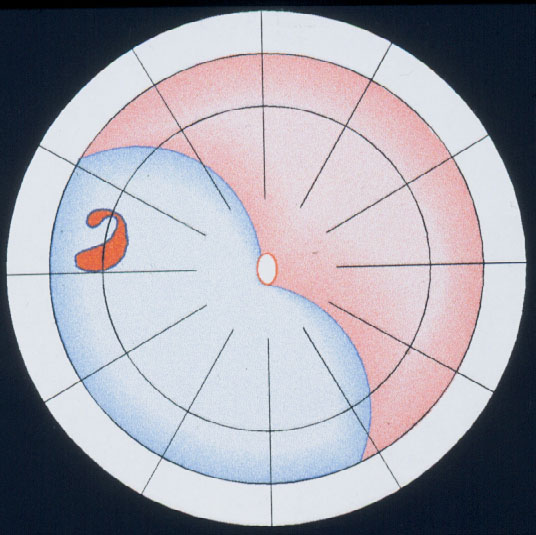

The balloon operation is the 3rd procedure for repair of a primary retinal detachment. New with the balloon operation is (1) that the buckle is not fixated by any suture and (2) that the balloon buckle is removed after 1 week. It can be applied for: detachments with 1 break or a group of breaks within 1 clock hour (Figure 11). The results after 1 balloon procedure are: Reattachment in 93 %, after balloon removal redetachment occurred within 6 months postoperatively at 2 %, but after reoperation reattachment increased to 99 % during a follow-up of 36 months [19]. After this atraumatic balloon operation the risk of postoperative PVR was further reduced to 0.2 %.

Figure 11. Indication for the balloon operation: A detachment caused by a single hole (top) or a group of breaks close together (bottom) which do not subtend more than 1 clock hour or 6 mm at the equator and which can be located at any clock hour, i.e., superiorly and inferiorly, but should be in the anterior 2/3 of the globe. (From A Practical Guide to Minimal Surgery for Retinal Detachment: Temporary Tamponades with Balloon and Gases without Drainage, Buckling versus Gases versus Vitrectomy, Reoperation, Case Presentations by Ingrid Kreissig. Thieme Stuttgart, New York, 2000, 9: 6, Figure 9.12)

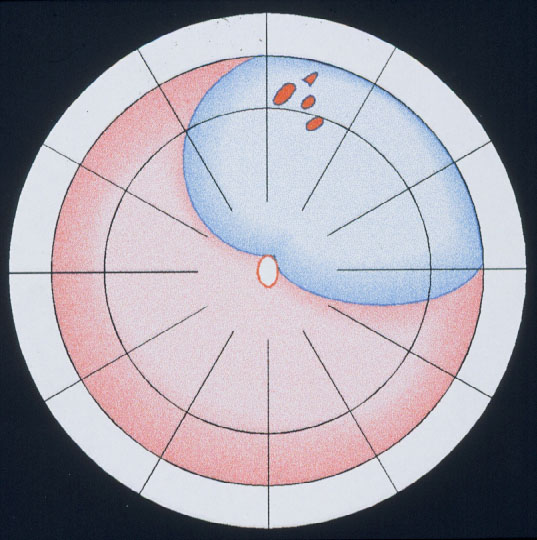

Parallel to these refinements in segmental buckling without drainage, it was found, that giant tears were not suitable for buckling. The long circumferential buckles caused constriction of the globe with leaking radial folds resulting in posterior redetachment. Therefore, Edward Norton in 1973 together with Harvey Lincoff in 1974 introduced for these giant tears, instead, an intraocular gas bubble as tamponade [20, 21]. After drainage of subretinal fluid, the gas SF6 was injected into the eye and the edges of the tear sealed off with cryopexy or with laser coagulation after reattachment (Figure 12). However, with this SF6-gas operation the great achievement of nondrainage was given up again, because prior to the gas injection, drainage of subretinal fluid was required to obtain the needed volume for the intraocular gas injection.

Figure 12. A gas bubble of SF6 after drainage of subretinal fluid as intraocular tamponade for reattaching a giant tear in a retinal detachment (by courtesy of Harvey Lincoff, MD, New York, 1976)

The 6th conceptional progress in the repair of a retinal detachment was made by Ingrid Kreissig [22–24] in 1979 with the expanding-gas-operation by injecting the intraocular gas without prior drainage of subretinal fluid. Since 1974, she had started to search for a possibility to sustain the concept of nondrainage for the intraocular gasoperation. After a preceding ocular compression, it became possible to inject 0.4 ml of SF6 without prior drainage and since the SF6-gas was expandable, its intraocular volume subsequently increased twice to 0.8 ml. This new expanding-gas operation was applied to detachments with giant tears and posterior breaks, but postoperative PVR had extremely increased (Table 1).

Table 1. The expanding-gas-operation without drainage of subretinal fluid, introduced by Ingrid Kreissig in 1979, as treatment for problematic retinal detachments. (From Clinical experience with SF6-gas in detachment surgery by Ingrid Kreissig. Ber Dtsch Opthalmol Ges. 1979;76:553–560)

| Detachment | N | Attached | PVR |

| Giant tear (75°–195°) | 9 | 6 | 3 |

| Post. hole(s) | 3 | 3 | - |

| PVR-detachm. | 3 | - | 3 |

| Total | 15 | 9 | 6 (40 %) |

Therefore, this expanding gas-operation without drainage was reserved for detachments with complicated breaks, but not used for detachments with uncomplicated breaks.

Why? Because (1) the rate of postoperative PVR after the intraocular gas-operation was too high and (2) because at that time there was already available the balloon procedure with practically no postoperative PVR, i.e., it ranged only at 0.2 % in comparison.

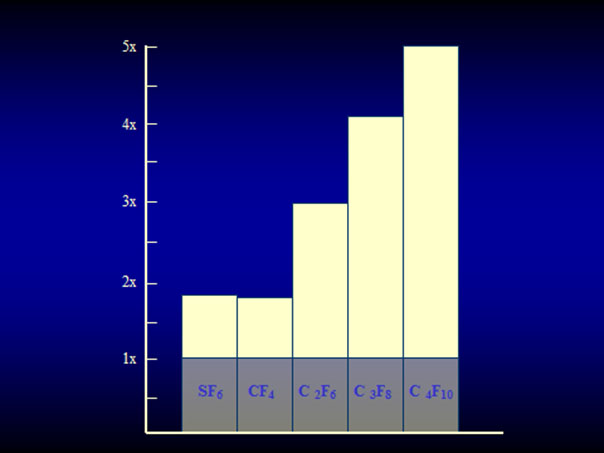

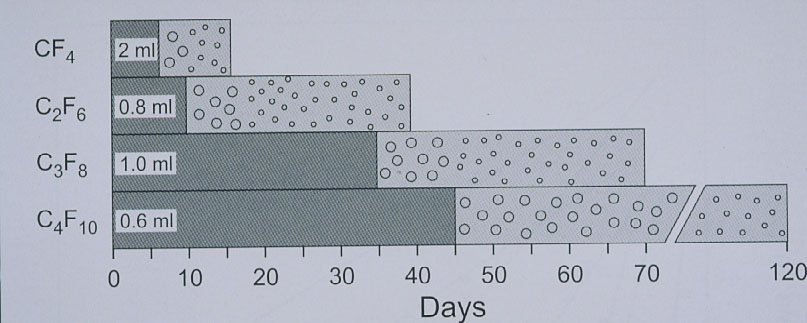

The expanding gas-operation without drainage, reserved for complicated tears, was further improved with the introduction of the perfluorocarbon gases by Harvey Lincoff and his group in 1980 [25]. The rate of expansion of the various perfluorocarbon gases are as follows: It ranges at 2× for CF4 and SF6 and for the other gases between 3.3× up to 5× of their original volume (Figure 13) [25]. However, a gas with a larger expansion is combined with a longer intraocular duration, which – as to be expected – results in an even higher rate of PVR (Figure 14) [26].

Figure 13. Expansion of the 4 straight-chain perfluorocarbon gases and SF6 in patient eyes. SF6 and CF4 have an expansion coefficient of 1.9×, C2F6 of 3.3×, C3F8 of 4×, and C4F10 of 5×. (From A Practical Guide to Minimal Surgery for Retinal Detachment: Temporary Tamponades with Balloon and Gases without Drainage, Buckling versus Gases versus Vitrectomy, Reoperation, Case Presentations by Ingrid Kreissig. Thieme Stuttgart, New York, 2000, 10: 130, Figure 10.9)

Figure 14. Disappearance time of the 4 straight-chain perfluorocarbon gases in patient eyes. The left portion of each bar (darker grey) indicates the time taken for the expanded volume of gas to diminish to half volume. Half-life of CF4 ranges at 6 days, of C2F6 at 10 days, of C3F8 at 24 to 35 days, and of C4F10 at 45 days. (From A Practical Guide to Minimal Surgery for Retinal Detachment: Temporary Tamponades with Balloon and Gases without Drainage, Buckling versus Gases versus Vitrectomy, Reoperation, Case Presentations by Ingrid Kreissig. Thieme Stuttgart, New York, 2000, 10: 125, Figure 10.6)

But despite the higher rate of postoperative PVR after the intraocular gas, the expanding-gas-operation without drainage, introduced by Kreissig in 1979, was re-introduced in 1986 by Dominguez [27] and Hilton [28], but now it was called pneumatic retinopexy and from now on it was used for uncomplicated detachments.

Pneumatic Retinopexy is the 3rd surgery still in use today for repair of a primary retinal detachment. The reattachment rate after pneumatic retinopexy for uncomplicated detachments is: 91 %, however, after disappearance of the gas, reattachment is reduced to 80 %, yet after several reoperations it is increased to 99 %. But – as complication – after this intraocular gas there are: New breaks in 15 % and postoperative PVR in 4 %.

The 7th Conceptional Progress in repair of a retinal detachment was made by Robert Machemer in 1972 [29] by introducing the vitrectomy and he had developed it for detachments with PVR (Figure 15).

|

|

Figure 15. Robert Machemer who introduced the vitrectomy for detachments with PVR in 1972

Due to my earlier 3-year long training in New York with Harvey Lincoff, in 1975 in Bonn we obtained the 1st outcome of a vitrectomy-instrument being shipped from USA to Europe. But just at that time Ingrid Kreissig was deeply involved in the new minimal segmental buckling without drainage with a minimum of complications and favourable results and as a consequence she had not so many cases with postoperative PVR which would have been the indication for a vitrectomy, nor were there many perforating injuries to use for them this new vitrectomy. Because eyes with foreign bodies and perforating injuries were sent to Neubauer in Cologne, 12 miles North from Bonn, where he had developed a new technique for localizing and removing nonmagnetic intraocular foreign bodies. Therefore, Ingrid Kreissig contacted Neubauer and his senior Heimann in Cologne, and offered to them her new vitrectomy instrument with the suggestion to use it on their numerous trauma eyes. Subsequently Heimann in Cologne became more involved in vitreous surgery and we in close-by Bonn in extraocular minimal segmental buckling without drainage for repair of retinal detachments.

In 1985 it was somehow concluded that an additional vitrectomy, now called primary vitrectomy, performed prior to pneumatic retinopexy, might reduce the high rate of postoperative complications after the gas injection.

Primary Vitrectomy is the 4th procedure still in use today for repair of a primary retinal detachment. It was applied to reduce the postoperative PVR and the development of new breaks after pneumatic retinopexy. However, this was not achieved, at least not up to now, since postoperative PVR after primary vitrectomy still ranges at 11.5 % and after a more recent metaanalysis still at 5.3 % and in addition, the rate of reoperations after primary vitrectomy ranged at first at 24.5 % and after more experience and by using more refined instruments according to a recent metaanalysis of Lincoff, still at 13.3 % with a resulting cataract.

In a subsequent risk ratio analysis of 3,384 intraocular procedures versus 1,854 extraocular procedures, Harvey Lincoff [30] could verify that the rate of reoperations after intraocular surgery is 2.5× higher than after extraocular surgery and the rate of postoperative PVR even 6× higher after intraocular surgery than after extraocular surgery.

In a Multicenter Study [31] in Europe, comparing the results after primary vitrectomy for medium difficult retinal detachments with those after scleral buckling, the results were:

– In phakic eyes, the functional results after scleral buckling are better than after primary vitrectomy.

– In pseudophakic eyes the results are better, but only if a cerclage is added, yet after several reoperations the results after both procedures are comparable.

Therefore, if there is a retinal detachment in a phakic eye, the prognosis is better and with less reoperations after scleral buckling than after primary vitrectomy.

In the year 2018 we have available for repair of a primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: 2 extraocular and 2 intraocular options. But to succeed with any of these methods, still the leaking break has (1) to be found and (2) sealed off sufficiently.

But for every of the 4 presented procedures, which can be selected for repair of a primary retinal detachment, the following 4 requirements have to be fulfilled:

1. To achieve retinal reattachment already with 1 operation.

2. To achieve this with a procedure with a minimum of morbidity.

3. To perform this surgery on a small budget and under local anesthesia.

4. Not to induce secondary complications that might jeopardize regained visual function during long-term follow-up.

CONCLUSION

When considering the presented issues, it might be even possible that the pendulum of detachment surgery, as we just could witness during the past 85 years, might swing back again to an extraocular surgery, in this case – I mean – back to minimal segmental buckling without drainage, limited to the area of the break and with a minimum of morbidity. But also on the other end of the spectrum there might evolve as treatment modality a minimal vitrectomy with less postoperative complications and this after further refinement of the minimal gauge instruments and the technique for vitrectomy.

Therefore, let us be open for new upcoming developments in retinal and vitreous surgery, but always with an eye on the accompanying morbidity and the postoperative long-term complications which could jeopardize the long-term visual function of our patients treated.

REFERENCES

- Gonin J. Le traitement opératoire du décollement rétinien. Conférence aux journées médicales de Bruxelles. Bruxelles-Médical 1930;23:No 17.

- Guist E. Eine neue Ablatiooperation. ZtschAugenheilk. 1931;74:232–42.

- Lindner K. Ein Beitrag zur Entstehung und Behandlung der idiopathischen und der traumatischen Netzhautabloesung. Graefes Arch Ophthalmol. 1931;127:177–295.

- Safar K. Behandlung der Netzhautabhebung mit Elektroden fuer multiple diathermische Stichelung. Dtsch Ophthalmol Ges. 1932;39:119.

- Rosengren B. Ueber die Behandlung der Netzhautabloesung mittelst Diathermie und Luftinjektion in den Glaskoerper. Acta Ophthalmol. 1938;16:3–42.

- Schepens CL. Prognosis and treatment of retinal detachment. The Mark J Schoenberg Memorial Lecture. A review by Kronenberg B, New York Society for Clinical Ophthalmology. Am J Ophthalmol. 1953;36:1739–56.

- Pruett RC. The fishmouth phenomenon: II. Wedge scleral buckling. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95(10):1782–7.

- Custodis E. Bedeutet die Plombenaufnaehung auf die Sklera einen Fortschritt in der operativen Behandlung der Netzhautablösung? Berichte der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft. 1953;58:102–5.

- Lincoff H, Baras I, McLean J. Modifications to the Custodis procedure for retinal detachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1965;73:160–3.

- Lincoff H, O’Connor P, Kreissig I. Die Retina-Adhaesion nach Kryopexie. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1970;156:771–83.

- Kreissig I, Lincoff H. Ultrastruktur der Kryopexieadhaesion. In: DOG Symp. “Die Prophylaxe der idiopathischen Netzhautabhebung”. Bergmann, Muenchen, 1971:191–205.

- Kreissig I, Lincoff H. Mechanism of retinal attachment after cryosurgery. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK. 1975;95:148–57.

- Lincoff H, Gieser R. Finding the retinal hole. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;85:565–9.

- Lincoff H, Kreissig I. Extraocular repeat surgery of retinal detachment. A minimal approach. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1586–92.

- Lincoff H, Kreissig I. Advantages of radial buckling. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;79:955–7.

- Kreissig I, Rose D, Jost B. Minimized surgery for retinal detachments with segmental buckling and nondrainage. An 11-year follow-up. Retina. 1992;12:224–31.

- Kreissig I, Simader E, Fahle M, Lincoff H. Visual acuity after segmental buckling and non-drainage: a 15-year follow-up. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1995;5:240–6.

- Lincoff HA, Kreissig I, Hahn YS. A temporary balloon buckle for the treatment of small retinal detachments. Ophthalmology. 1979;86:586–92.

- Kreissig I, Failer J, Lincoff H, Ferrari F. Results of a temporary balloon buckle in the treatment of 500 retinal detachments and a comparison with pneumatic retinopexy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;107:381–9.

- Norton EWD. Intraocular gas in the management of selected retinal detachments. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1973;77:85–98.

- Lincoff H. Reply to Drs Fineberg, Machemer, Sullivan and Norton. Mod Probl Ophthalmol. 1974;12:344–5.

- Kreissig I. Clinical experience with SF6-gas in detachment surgery. Berichte der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft. 1979;76:553–60.

- Kreissig I, Stanowsky A, Lincoff H, Richard G. Treatment of difficult retinal detachments with expanding gas bubble without vitrectomy. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1986;224:51–4.

- Kreissig I. The expanding-gas operation after 15 years: Data of animal experiments, subsequent modifications of the procedure and clinical results in the treatment of retinal detachments. Klin Mbl Augenheilk. 1990;197:231–9.

- Lincoff A, Haft D, Liggett P, Reifer C. Intravitreal expansion of perfluorocarbon bubbles. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:1646.

- Lincoff H, Maisel JM, Lincoff A. Intravitreal disappearance rates of four per-fluorocarbon gases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:928–9.

- Dominguez A, Fonseca A, Gomez-Montana J. Gas tamponade for ambulatory treatment of retinal detachment. In: Proceedings of the XXVth International Congress of Ophthalmology. Rome, May 4–10, 1986. Kugler & Ghedini, Amsterdam, 1987:2038–45.

- Hilton GF, Grizzard WS. Pneumatic retinopexy. A two-step outpatient operation without conjunctival incision. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:626–41.

- Machemer R, Buettner H, Norton EWD, Parel JM. Vitrectomy: a pars plana approach. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol. 1971;75:813–20.

- Lincoff H, Lincoff A, Stopa M. Systemic review of efficacy and safety of surgery for primary retinal detachment. Primary retinal detachment: Options for repair, Springer 2004, chapter 8. 161–75 (Ed. Kreissig)

- Heimann H, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Bornfeld N, Weiss C, Hilgers RD, Foerster MH. Scleral buckling versus primary vitrectomy in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a prospective randomized multicenter clinical study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1634–5.